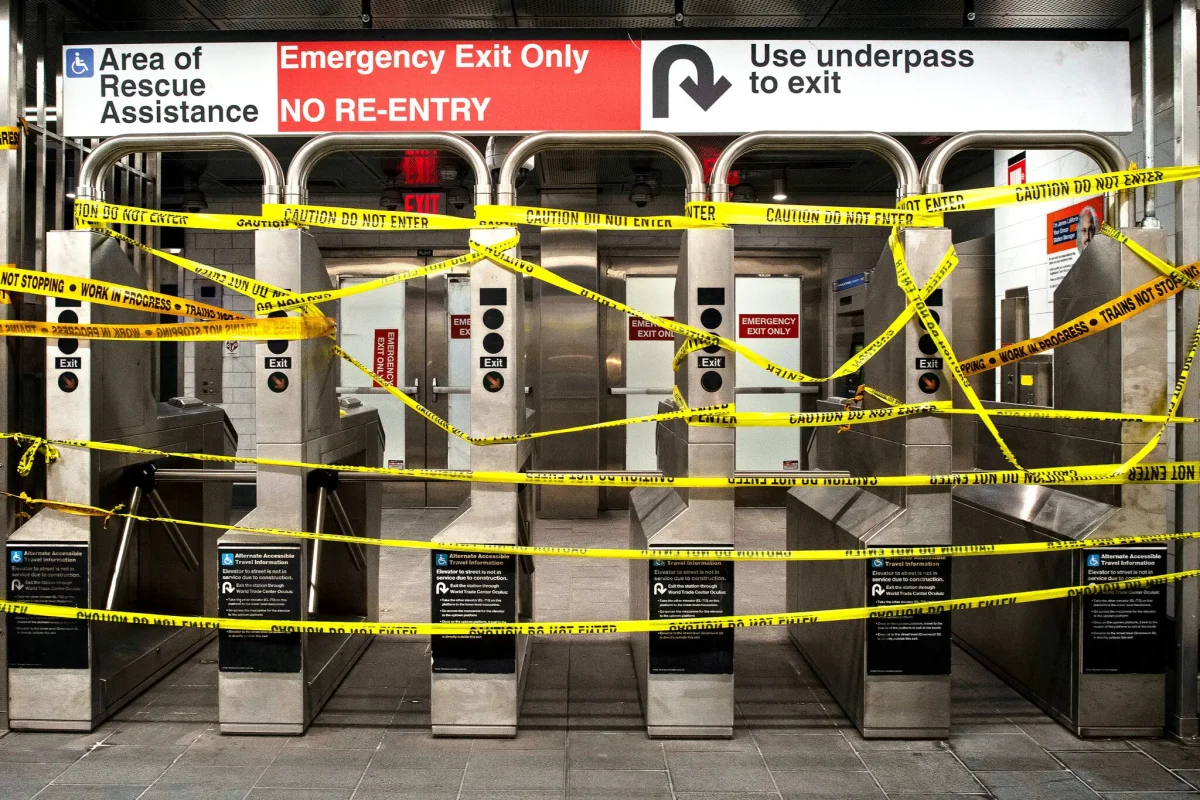

On September 16th, after an incident involving a suspected fare evader at an L-Train Station in Brownsville, Brooklyn, NYPD officers shot four people, which included one officer shot in friendly fire. The man in question, 37-year old Derell Mickles, was killed and an innocent bystander shot in the head by officers is now said to have potential brain damage. The shooting is part of a larger push by NYPD and NYC authorities alongside the MTA to crack down on fare evasion.

Janno Lieber, chief executive of the MTA, called fare evasion “the No. 1 existential threat” for the MTA. Fittingly, it has been part of a larger financial crisis for the agency, the largest public transportation agency in North America. Since 2017, and especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, fare evasion has increased drastically. According to Lieber himself, the cost of fare evasion has more than doubled since 2022, having cost the MTA about $690 million in lost profits in 2023 alone.

This rise in fare evasion, although an issue facing the subway system, has primarily happened on MTA buses. As the MTA’s fare evasion metrics indicate, while in the second quarter of 2024, only about 14% of subway riders did not pay the fare, relatively the same amount as the past four years; 49% of bus riders didn’t pay the fare in the same time frame, more than twice the amount as in 2020. This issue is even more pronounced on select bus services, wherein 57% of riders evaded the fare. This rise also serves as part of the MTA’s larger budgeting crisis, with fare revenue overall serving as 26% of the agency’s revenue source. Accordingly, the MTA has been facing a $900 million deficit crisis and, as a part of it, has rolled back bus service in several boroughs, express bus service in particular.

The question of what to do about this rise in fare evasion has also emerged recently. Various different approaches have been taken throughout the city’s public transit system. In many select service buses, MTA fare enforcement officers have taken to stopping buses at random points to check passengers for physical tickets or scan their phones for proof of payment. While this crackdown, still in its early stages, may help limit some fare evasion, various issues still exist within the plan, such as the fact that this requires a great deal of manpower as well as the technicality behind defining “random” stops. The punishment for fare evasion has also become more severe, which may serve to deter future acts of fare evasion.

While the exact solution to solve the rise in fare evasion is still being figured out, many advocates have reiterated one thing: Harsh and violent over policing of fare evasion is not the answer. Michael Sisitzky, assistant policy director at the New York City Civil Liberties Union, added in an interview with Mother Jones, “What happened [in the Brownsville shooting] is an inevitable outcome of that kind of tough-on-crime approach, where the only tool that we seem to have to offer is police officers, who are going to focus on enforcement and if they’re given an aggressive mandate to enforce, are going to enforce that aggressively. […] That is such a mismatch we don’t need to be constrained thinking about responding to fare evasion with just a police law enforcement tool.”

“We should be thinking more broadly about getting people access to the support they need to enroll in programs for New Yorkers who can’t afford to pay for fares to get to work, pay for child care, or get access to medical care,” Sisitzky said.