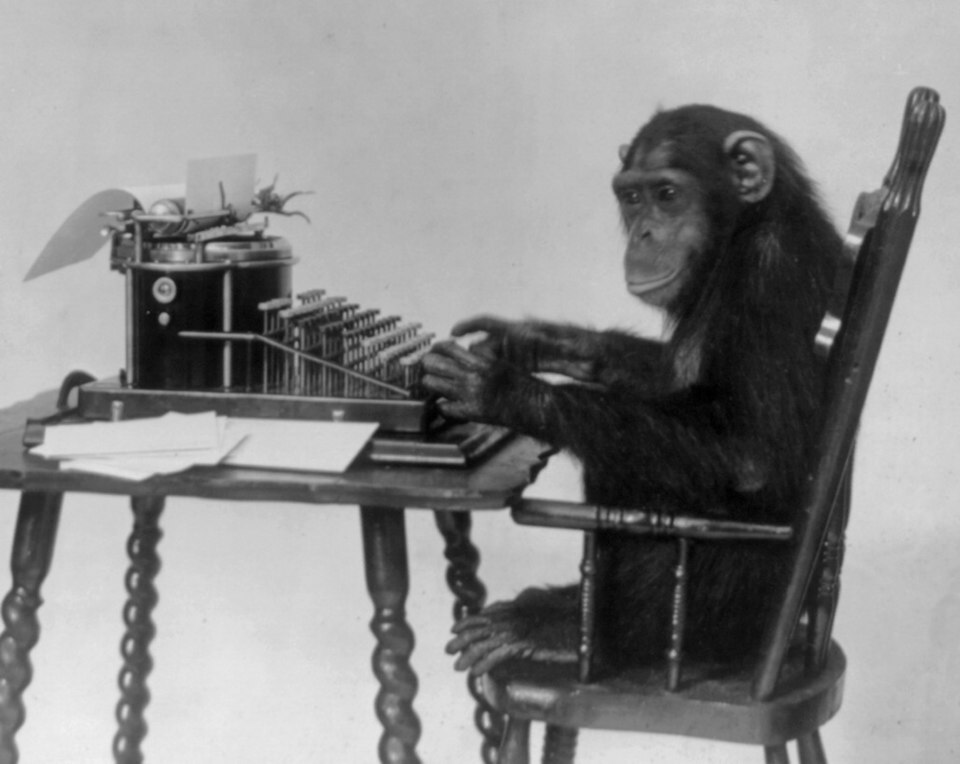

Monkeys. They aren’t necessarily our ancestors, but they are close enough to be in the same family. They are smart enough to form pack bonds, complete tasks if given reinforcement, and even learn sign language if they work hard enough. Now imagine thousands of hundreds of monkeys all in a line in front of a typewriter. A weird image, right?

The sound of clicking keys on end (with the occasional chirp or hoot) will fill the hallway as the monkeys randomly type whatever letters tickle their fancy. This unstructured chaos of a scenario will go on for a very long time. Centuries maybe? Millennia? Eons?

What if I told you that any of these monkeys would eventually recreate anything that has ever been written? Assignments, emails, and even the assigned books you read in class.

This is the basis of the Infinite Monkey Theorem created by French mathematician Émile Borel. Borel claims that a monkey could hypothetically write William Shakespeare if given infinite time and infinite resources. No, not just the name (even though that’s a step toward the bigger picture). I mean the Complete Works of William Shakespeare with virtually no errors.

So, what does that mean for Shakespeare? Do his masterpieces lose their merit if they could be re-written or mindlessly typed by a monkey? How significant is the difference between reproducing a string of words on a page (which any large language model can do) and creating an original work? To answer this question, we first have to answer a much broader one: Why do we write in the first place? Let’s take a deep dive.

Our story starts in Ancient Mesopotamia with proto-cuneiform, a form of language that consisted of symbols (similar to how we use the alphabet today) written on clay tablets. This is the earliest system of writing that we know of today.

Like many forms of early writing, proto-cuneiform was used for bureaucratic purposes to manage livestock, trade, and the stock of goods. As word of mouth spread, this writing system evolved and even branched into different writing systems, like hieroglyphics.

From there, many new systems appeared, but none as important as the Phoenician alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet led to many systems of writing that predate languages used today, such as Greek and Latin. Their importance? They gave rise to the beginnings of the English language.

So, what’s the point? With so many words, letters, and characters, why do the ones we use matter? Do the ones that I use matter?

As time advances, I can tell a bot to put words together and write this article. I go on these deep dives and hope something will stick to the wall, meanwhile a bot could write this article instantly without issue.

If I was a machine, I would use and write my words perfectly with correct verbs, adjectives, and nouns. If I were a machine, I’d write without fear of critique and have the motivation to write whether the topic was boring, fun, or annoying. I’d always find the answer.

But I’m not a machine. Like many people, I’m always waiting for a better time to write, yet that better time never quite arrives. Does the said “better time” even exist?

So if artificial intelligence can write a perfect article instantly and a monkey could write the same with little to no thought, why do we write?

Both parties lack one thing: a why. Sure, you give the monkey positive reinforcement and the AI a directive, but it lacks the feelings and desperation that make all these words worth something.

When one reads Shakespeare, one can feel the connection between his life and his works—the tragedy and humor that can only be informed by human experience. AI can simulate that experience and a monkey can type the words, but it won’t ever understand that experience as a human would.

For as long as we can write, we’ve used it to connect with others, whether to establish trade or write a love letter. Writing is history, telling us stories and cautionary tales of those who came before us so that we can be better.

Writing is an outlet that allows others to look through the eyes of a character, another person, and explore human feelings, whether that be anger, sadness, relief, or joy. Writing is an escape that allows us to take a break from the world outside, if only for a moment.

We write to leave a mark on this world, a big metaphorical red arrow that says “I WAS HERE!” in big bold letters. Writing is the solution to the instinctual fear of being forgotten.

So, yes. A monkey or AI could hypothetically write this article or the Complete Works of William Shakespeare. The issue is that neither of us could ever truly understand the magnitude of what’s being written as we do. Words aren’t meant to be meaningless; they’re meant to rebel against the unfair, stand up for the just, change minds, and touch hearts.

That’s why we write. For love, for history, and for the understanding of what being alive truly means.